Twain in Buffalo

mARK tWAIN’S tIME IN bUFFALO

It can be said that the story of Mark Twain’s association with Buffalo, New York, begins and ends at the J. Langdon & Co. coal yard on Buffalo’s bustling waterfront. Mark Twain’s future father-in-law, Jervis Langdon, operated a key branch office of his prosperous Elmira-headquartered anthracite coal business in Buffalo. That city was strategically located at the western terminus of the Erie Canal.

The Langdon & Co. office was at 221 Main Street in Buffalo’s business district, but the coal yard was located at the foot of Genesee Street, between the canal and Lake Erie. Coal-laden canal barges could unload their cargo at the yard for shipment to customers across the Great Lakes—a north-south slip ran alongside the coal yard connecting the canal and lake. The Langdon yard also featured a spur of the New York Central Railroad, so that trains could drop off and pick up coal for delivery in any geographical direction.

In early August of 1869, Twain took a short train trip from Niagara Falls, New York, to Buffalo with Jervis Langdon. They toured Langdon’s coal facilities together—the branch office and the waterfront coal yard. Then, they stopped in at the Buffalo Express at 14 East Swan Street so that Langdon could examine the newspaper’s financial situation. He came away satisfied that the Express would be a sound investment for his future son-in-law to buy into.

Twain had already spent two days in Buffalo in mid-July, checking out the city and the Express. While in town, he assisted Langdon’s trusted Buffalo office executive, John De La Fletcher Slee, with negotiations for the likely transaction and he observed that “the private residences of Buffalo are the finest in the country.” In seven months he would live in one of them.

Twain and Olivia Langdon had gotten engaged four months earlier. The “newspaper job sweepstakes” for Twain began immediately thereafter. He had a keen interest in joining the Cleveland Herald, which had an ownership share available for $25,000. Twain also considered buying into the Hartford Courant and the Toledo Blade.

But Jervis Langdon engineered Twain’s decision in favor of Buffalo. After all, with Twain living and working in Buffalo, Langdon’s daughter would be only a 4-hour train ride from Elmira. Furthermore, Buffalo’s booming rail and shipping hub was advantageous to his business growth, and his Buffalo branch employees could help Twain settle in, as well as keep an eye on the “Wildman of the Pacific Slope” during his remaining days of bachelorhood. By the end of July, Langdon had convinced Twain that the Cleveland Herald asking price (twice that of the Express) was too high. However, he would stake Twain one half the Express’s purchase fee of $25,000 and guarantee the rest. Unable to resist that offer, Twain headed to Buffalo for gainful employment as a newspaper co-owner and managing editor.

He moved into a one room apartment at Mrs. J.C. Randall’s large, respectable boarding house at 39 East Swan Street, just steps away from the Express. Also living there were John J. McWilliams and his wife, Esther. McWilliams was a clerk at J. Langdon & Co., and Esther handled Twain’s laundry.

On August 14, Twain closed the deal to acquire one-third ownership of the Express and was feted as guest of honor at the Western New York Press Club annual dinner. He entertained his new local journalism fraternity members by reading from his newly-published The Innocents Abroad.

For the next six weeks, Twain energetically put into place several innovations. He worked with composing room foreman John Hall to transform the look of the newspaper. He enlisted staff artist John Harrison Mills to draw illustrations that accompanied his own comical Saturday feature stories. He groomed cub reporter Earl Berry to infuse zest into previously dry police court coverage. He revamped the stodgy compendium of news briefs by personally combing newspaper exchanges for offbeat tidbits and compiling them into a highly entertaining “People and Things” column. In the absence of fellow co-owner, and political editor Josephus N. Larned, he even took it upon himself to write a flippant, satirical “endorsement” of the Republican state secretary—a story that had to be repaired when Larned returned.

In his first six weeks Twain published over one-third of the work he produced in the entire seventy-six weeks he was affiliated with the Buffalo Express, a period which ended in March 1871.

Twain’s amusing Saturday feature stories in the fall of 1869 were a mix of fact and fiction, a technique that he continued successfully from the style of The Innocents Abroad. In a two-part series on visiting Niagara Falls, and in stories such as “Journalism in Tennessee,” he borrowed comic gimmicks from The Innocents Abroad, particularly adopting the narrative persona of gullible “Inspired Idiot.”

However, his initial enthusiasm for the Express gave way to a perceived need to earn money in advance of his upcoming February marriage to Olivia. From November 1869 through mid January of 1870, Twain hit the lecture trail, scheduling fifty appearances throughout the northeast. While on the circuit, he continued to send regular contributions to the Express.

On February 3, 1870, a day after a private wedding ceremony held in the huge Langdon home in Elmira, Twain and his bride arrived back in Buffalo, where Twain was dazzled by a surprise wedding gift. Olivia’s parents had purchased a semi-mansion on Buffalo’s prestigious Delaware Street, equipped with maid, cook, and coachman. With that, Twain’s days of slaving in his cramped third floor Express office came to an end. From then on, he mostly wrote in his upstairs den at home and a courier delivered his stories several blocks away to the Express. In fact, several of his best stories in 1870 were based on neighborhood topics, such as his hilarious two-part spoof , “A Curious Dream,” inspired by a nearby dilapidated cemetery.

When Jervis Langdon was diagnosed with stomach cancer in spring 1870, Twain and Olivia frequently shuttled between Buffalo and Elmira to be at his bedside. After he died in August, Olivia was overcome by grief. Emma Nye, a childhood friend, visited their Delaware Street home to comfort Olivia, but contracted typhoid fever and died in their master bedroom on September 29.

More tragedy followed.

Three weeks later Olivia had a near miscarriage. In early November, Olivia gave birth to a son, Langdon. He was born a month premature, weighed only 4 ½ pounds, and was in precarious health every day for the remaining four months that the family resided in Buffalo. Olivia was bedridden with poor health and by February 1871 exhibited signs of typhoid.

Twain’s contributions to the Express and the New York City-based literary magazine Galaxy tailed off dramatically. The promising start he had made in Buffalo on his next book Roughing It was also curtailed. Their Delaware Street home was listed for sale, and on March 18, with Olivia carried out of the house on a mattress to a waiting carriage, Twain and his family were taken to Buffalo’s Exchange Street depot for a temporary move to Elmira. Their life in Buffalo ended.

Twain’s Buffalo period—August 1869 until March 1871–has traditionally been dismissed as inconsequential, unproductive and lonely, with Albert Bigelow Paine setting the tone in his 1912 biography. But recent scholarship has revealed new insights. Although away from his Express desk for long stretches, his output at the newspaper included nearly thirty editorials and over seventy stories (several of them on a par with his writing in The Innocents Abroad), reviews, letters and shorter pieces. He also compiled sixteen “People and Things” columns, and began work on Roughing It. With royalties from The Innocents Abroad streaming in, and with Olivia’s substantial inheritance in hand, Twain’s time with the Buffalo Express marked his important career transition from fulltime journalist to a man of letters.

While in Buffalo, Twain also cultivated a significant social and professional network of clerics such as Grosvenor Heacock and John Lord, journalists such as Larned, Mills and David Gray, businessmen such as Slee, McWillams and Charles Underhill, and politicians such as Grover Cleveland, who remained lifelong friends.

Over the ensuing years, Twain returned to Buffalo several times for speaking engagements and to visit friends.

After Olivia’s death in 1904, Twain—as her executor—inherited her partnership in J. Langdon & Co. and as such co-owned the old Buffalo coal yard property for the final six years of his life. J. Langdon & Co. no longer had a footprint in Buffalo, but it still owned and rented out the valuable waterfront land. During those years, Twain’s share of the rent collected probably did not equal the amount he had to pay for his share of city and county property taxes.

Thus, the J. Langdon & Co. coal yard brings the story of Mark Twain in Buffalo full circle.

(This entry is from the Center for Mark Twain Studies website.)

Photo credit: Samuel Langhorne Clemens, head-and-shoulders portrait, Abdullah Fréres, photographer, 1867. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-28851 (b&w film copy neg. of recto) LC-USZ62-137978.

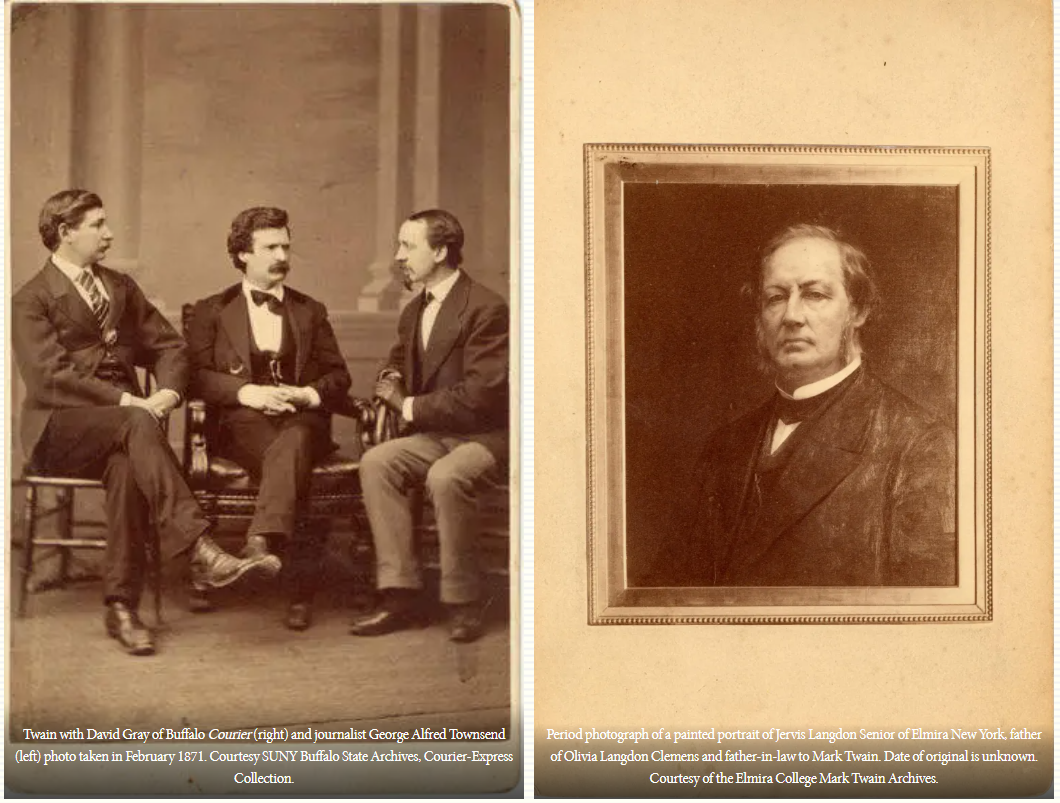

Twain with David Gray of Buffalo Courier (right) and journalist George Alfred Townsend (left) photo taken in February 1871. Courtesy SUNY Buffalo State Archives, Courier-Express Collection. Period photograph of a painted portrait of Jervis Langdon Senior of Elmira New York, father of Olivia Langdon Clemens and father-in-law to Mark Twain. The date of the original is unknown. Courtesy of the Elmira College Mark Twain Archives.

1863 drawing of J. Langdon & Co./Anthracite Coal Association coal yard and slip at Buffalo harbor. Courtesy Chuck LaChiusa.

Buffalo Express at 14 East Swan Street—narrow four-story building second from left. Courtesy Buffalo History Museum.

Buffalo Express at 14 East Swan Street—narrow four-story building second from left. Courtesy Buffalo History Museum. 472 Delaware Street, wedding gift where Twain and Olivia lived from February 1870 to March 1871. Courtesy Buffalo History Museum.